Does the US Military Have Enough Minerals for a US-China War?

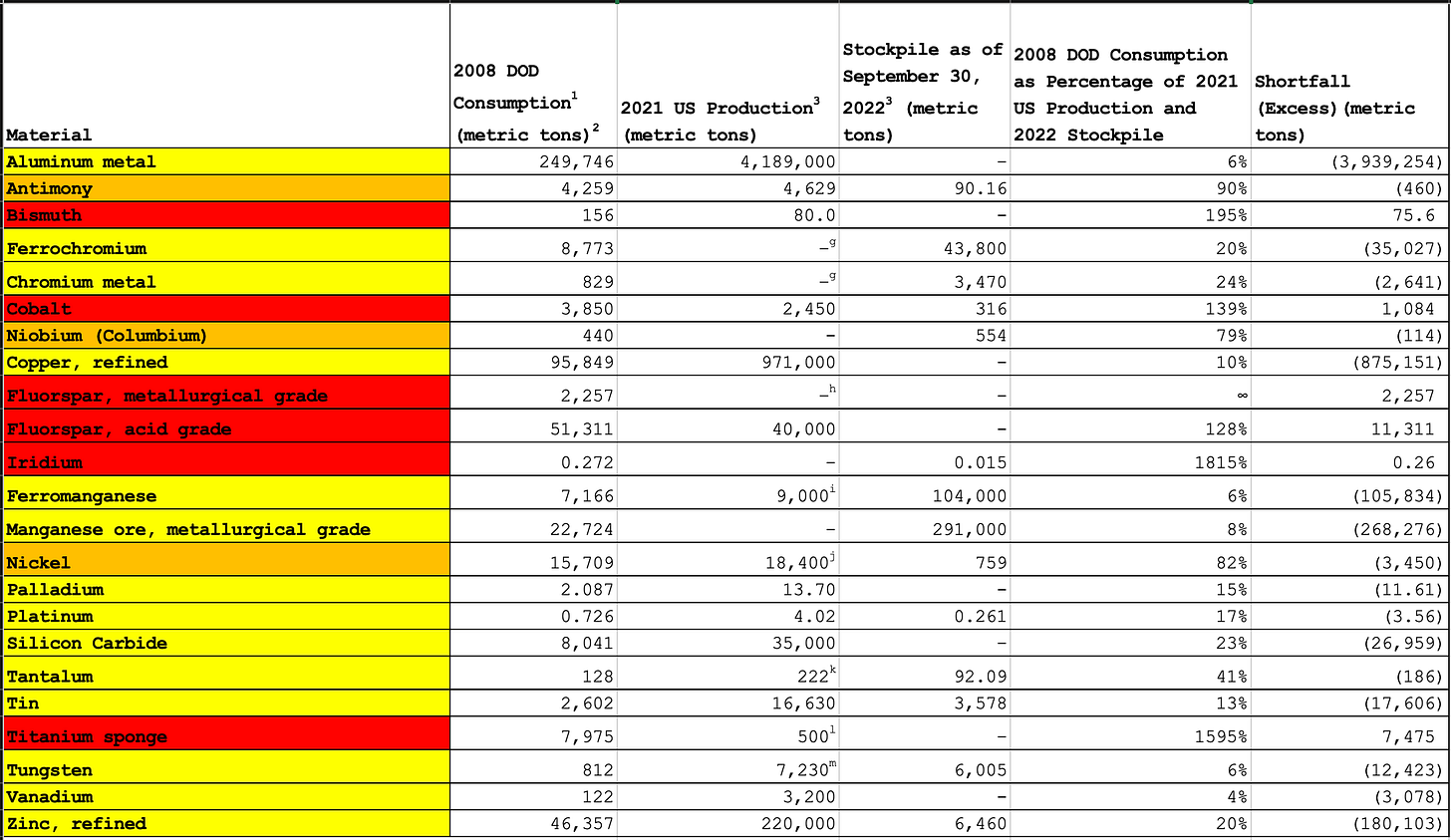

The materials with the highest shortfall risks include antimony, bismuth, cobalt, niobium, metallurgical-grade fluorspar, acid-grade fluorspar, iridium, nickel, and titanium sponge.

Note: On December 5, 2023, a counterarguments section was added to the end of the article, discussing possible risks of publicly releasing stockpile information.

The National Defense Stockpile is increasingly mentioned as a tool to both reduce America’s reliance on foreign materials, especially materials from China, and prepare for a possible US-China conflict. The stockpile, managed by the Department of Defense, contains materials like cobalt to support vital domestic industries during national emergencies like war. However, the Department of Defense does not publicly release its biennial stockpile assessment, which analyzes what materials may be in shortfall during a US-China war. And even if publicly released, the stockpile assessment—if the publicly available 2015 stockpile assessment is indicative—does not specifically delineate the military’s projected shortfall quantities for individual materials. The assessment only lists the total value of the military’s material shortfall, which combines the shortfalls for all materials, and the total shortfall values and quantities for individual materials, which combines the shortfalls from the military as well as industrial and essential civilian sectors.

Delineating the military’s projected shortfall quantities for individual materials would inform what materials—and corresponding applications—the US military will most likely have shortfalls of during a war. With such information, the defense industrial base could preemptively stockpile such materials before the outbreak of a conflict. To illustrate shortfall risks for individual materials, this article estimates the US military’s shortfall risks for twenty-three materials in three different war scenarios. It finds that the following nine materials have the highest shortfall risk: antimony, bismuth, cobalt, niobium (columbium), metallurgical-grade fluorspar, acid-grade fluorspar, iridium, nickel, and titanium sponge.

Current Shortfall Assessments

Material shortfalls can impact—and have impacted—US warfighting ability. Kenneth Kessel writes in Strategic Minerals: U.S. Alternatives, “The record shows that the US capability to wage war in the past has in some cases been impinged on by a lack of adequate supplies of strategic minerals—in large measure because of a national stockpile that was insufficient (a) to offset supply-line interdictions or (b) to bridge the gap between normal industrial output and the time necessary to gear up for the sharply higher output needed to support the war effort.” In three of its four largest wars—World War I, World War II, and the Korean War—the United States had material shortfalls.

The purpose of the National Defense Stockpile is to avoid shortfalls by storing extra materials to support important sectors during national emergencies like war. Under US law, the stockpile is “to provide for the acquisition and retention of stocks of certain strategic and critical materials and to encourage the conservation and development of sources of such materials within the United States and thereby to decrease and to preclude, when possible, a dangerous and costly dependence by the United States on foreign sources or a single point of failure for supplies of such materials in times of national emergency.” Simply put, the stockpile aims to reduce supply chain risk for the United States.

The Department of Defense monitors 283 materials for possible inclusion in the stockpile. It then seeks to stockpile materials expected to be in a shortfall for military, industrial, and essential civilian sectors during a one-year war with China, including an attack on the US homeland, followed by a three-year recovery. These shortfalls are calculated with models that integrate demand variables such as weapons platform requirements and supply variables such as foreign mineral imports. As noted by Cameron Keys in a Congressional Research Service report, the FY2023 stockpile assessment found that the military would have shortfalls in sixty-nine materials totaling $2.41 billion. With current stockpile inventories of $912.3 million, the stockpile would cover about 40 percent of the military’s projected material shortfalls.

However, the Department of Defense does not publicly release its biennial stockpile assessment, which analyzes what materials may be in shortfall during a US-China war. And even if publicly released, the stockpile assessment—if the publicly available 2015 stockpile assessment is indicative—does not specifically delineate the military’s projected shortfall quantities for individual materials. In other words, the general public does not know how much of a shortfall the military will have for individual materials during a war. The assessment only lists the total value of the military’s material shortfall, which combines the shortfalls for all materials, and the total shortfall values and quantities for individual materials, which combines the shortfalls from the military as well as industrial and essential civilian sectors. For example, the 2015 stockpile assessment estimates the total military material shortfall as $273 million with the base case war scenario, but the assessment does not include the quantity (or value) of the military shortfalls for individual materials. The 2015 stockpile assessment also lists the total shortfalls for individual materials, but it combines the shortfalls from the military, industrial, and essential civilian sectors—it does not specifically highlight the military shortfalls for individual materials.

Various US government-connected entities have emphasized the importance of understanding the US military’s material shortfall risks. In a 2008 report assessing the need for a military stockpile, the National Research Council of the National Academies said that the Department of Defense “would benefit from a serious near-term effort to capture specific defense materials needs,” concluding that the “Department of Defense appears not to fully understand its need for specific materials or to have adequate information on their supply.” The report added, “The committee is struck by the lack of coordination across the DoD [Department of Defense] and the military services to identify specific individual and shared materials needs.” The Institute for Defense Analyses, which assists the Department of Defense in stockpile assessments, in a 2009 report indeed calculated the military’s material usage and shortfall risks. The report stated that “it would be useful for the DoD [Department of Defense] to undertake these future assessments [on annual material usage] on a sustained basis.” Yet, such assessments have either not been undertaken or released publicly since.

Thus, this article focuses on the US military’s material shortfall risks specifically, excluding industrial and essential civilian shortfalls, because industrial and essential civilian sectors can do with less materials during a war, while material shortfalls for the military will impact US warfighting ability. As President Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote in a September 24, 1963, letter to Senator Clifford P. Case, explaining the rationale for his stockpile strategy during his presidency: “You will recall that, when we became involved in World War II, our lack of an adequate stockpile of strategic and critical materials gravely impeded our military operations. We were therefore forced into costly and disruptive expansion programs. The nation was compelled to divert, at a most critical time, scarce equipment and machinery and manpower to obtain the necessary materials.” Consequently, this article focuses on material shortfalls for the US military.

Understanding projected military shortfalls for individual materials is important because it will inform what materials and corresponding applications the US military will most likely have shortfalls of during a war. With such information, the defense industrial base could preemptively stockpile such materials before the outbreak of a conflict, enabling the defense industry to better support the US war effort. To illustrate the military’s material shortfall risks, this article estimates the military’s projected shortfall risk for twenty-three materials.

Methodology

To select the materials, I first gathered information on the Department of Defense’s annual material consumption. The most recent and comprehensive list is from an Institute for Defense Analyses assessment in the Department of Defense’s “Reconfiguration of the National Defense Stockpile Report to Congress” from April 2009, which includes thirty-five materials. From this list, I then selected those materials deemed as “critical materials” by the Department of Energy, which totaled twenty-three materials.

To calculate the military’s material consumption (i.e., demand), I proposed three different war scenarios with escalating material consumption. The first war scenario assumes that the Department of Defense’s material consumption in a US-China war would be at 2008 levels. The “Reconfiguration of the National Defense Stockpile Report to Congress” from April 2009 lists these consumption levels. The second war scenario assumes that the Department of Defense’s material consumption in a US-China war would be at estimated 2021 levels. Since the military’s most recent consumption data is from 2008, I had to estimate the military’s 2021 consumption. To do so, I used the Department of Defense’s procurement outlays as a reference, tying the military’s increase in material consumption to the real percentage increase in procurement outlays from FY2008 to FY2021. Since the Department of Defense spent $88.915 billion on procurement in FY2008 and $112.823 billion in constant 2008 dollars in FY2021—a 27 percent increase—I assumed the military’s material consumption increased by 27 percent from 2008 to 2021. The third war scenario simply assumes that the Department of Defense’s material consumption in a US-China war would be 25 percent more than the estimated 2021 levels.

Risks exist in using the military’s material consumption from fifteen years ago as a benchmark. At the time in 2008, the US military was focused on counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations in the Middle East, not a large-scale conventional war against a peer competitor. Thus, the military’s platforms, munitions, and material consumption in 2008 will vary from the military’s platforms, munitions, and material consumption in a prospective US-China conflict. Importantly, such a conflict would likely shift the US economy to a wartime economy. The Congressional Budget Office noted in September 1982 about cobalt, “Clearly, a wartime economy would require significantly greater defense-related expenditures in a number of industries that use cobalt. The slated defense buildup for the 1980s will probably increase the present peacetime need for cobalt.” Other materials would also have higher consumption levels in a large-scale conventional conflict. The 2008 consumption figures do provide insight, however, as US troop levels in Iraq reached their peak in 2008; consequently, the 2008 consumption figures offer the most recent numbers on the US military’s material consumption amid large-scale military operations.

To calculate the military’s material access (i.e., supply), I only considered the most recent US material production, which is from 2021, and National Defense Stockpile inventories, which are from September 30, 2022. The US Geological Survey provides these figures. Only considering domestically produced and stockpiled materials as supply sources differs from the government’s stockpile assessment, which also includes foreign supplies. I made this decision in order to assess the United States’ ability independent of foreign actors to satisfy its military’s material consumption. As previous national emergencies have revealed, the United States sometimes cannot rely on foreign countries, including defense allies, for critical supplies during national emergencies. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, US defense allies France and Germany imposed export restrictions on potentially life-saving personal protective equipment to the United States. Moreover, even if foreign countries do seek to supply materials to the United States in a US-China conflict, many of these countries, especially those in Asia, will face contested sea lines of communication. Thus, in this article, I assume that the US military can only access materials produced and stockpiled domestically.

Therefore, this article uses estimated Department of Defense material consumption, US material production, and National Defense Stockpile inventories, to estimate military shortfalls for twenty-three materials during three war scenarios. The shortfall quantity is calculated by first taking the Department of Defense’s estimated material consumption and then subtracting the sum of US material production from 2021 and National Defense Stockpile inventories from September 2022.

Department of Defense’s estimated material consumption – (US material production from 2021 + National Defense Stockpile inventories from September 2022) = Shortfall (Excess)

I also calculated the military’s projected material consumption as a percentage of the combined total for domestic production and stockpile inventories.

Department of Defense’s estimated material consumption / (US material production from 2021 + National Defense Stockpile inventories from September 2022) = US military material consumption as a percentage of US production and stockpile

Based on this calculation, I assigned a shortfall risk level for each material. If the material had a consumption percentage of 100 percent or greater when compared to both domestic production and the stockpile—that is, US military consumption for that material was greater than the combined total of the material produced and stockpiled in the United States—it was deemed high risk and highlighted as red. If the material had a consumption percentage of less than 100 percent but greater than 50 percent when compared to both domestic production and the stockpile, it was deemed medium risk and highlighted as orange. If the material had a consumption percentage of less than 50 percent but greater than 0 percent when compared to both domestic production and the stockpile, it was deemed low risk and highlighted as yellow.

Results

The article found that at 2008 material consumption levels, the US military has a high shortfall risk for six materials, a medium shortfall risk for three materials, and a low shortfall risk for fourteen materials.

To illustrate, the US military consumed 3,850 metric tons of cobalt in 2008, while the Department of Defense stockpiled 316 metric tons of cobalt as of September 2022 and the United States produced 2,450 metric tons of cobalt in 2021—most of which was exported outside the United States for refining. Thus, if the US military consumed the same amount of cobalt in a US-China conflict as it did in 2008, the military would have a shortfall of 1,084 metric tons, meaning the US military would have to rely on 1,084 metric tons of foreign cobalt imports to meet military demand. Given the high risks of supply chain disruption during a US-China conflict, these materials would not be a guaranteed supply source. Moreover, since the United States does not have significant cobalt refining capacity and cobalt ore has no applications unless it is refined, the domestic shortfall is more accurately 1,734 metric tons when cobalt ore is excluded as a supply source. In other words, the US military will have to rely on foreign imports for 1,734 metric tons of cobalt, if the US military’s cobalt consumption during the conflict is indeed 3,850 metric tons of cobalt. However, suppose the US military’s cobalt consumption is even higher due to higher attrition rates or higher use of cobalt-intensive components such as samarium-cobalt magnets and cobalt-based superalloys in jet engines. In that case, the shortfall will be even higher, making the US military rely even more on foreign imports—and placing cobalt at an even higher shortfall risk.

The article found that at estimated 2021 material consumption levels, the US military has a high shortfall risk for nine materials, a medium shortfall risk for one material, and a low shortfall risk for thirteen materials.

The article found that with a 25 percent increase to estimated 2021 material consumption levels, the US military also has a high risk of shortfall for nine materials, a medium shortfall risk for one material, and a low shortfall risk for thirteen materials.

Since one can rightly assume that the US military’s material consumption during a large-scale conventional US-China conflict in the future will be greater than the US military’s material consumption during counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations in 2008, we can assume that second and third war scenarios better illustrate potential US military material consumption during a US-China conflict and thus potential US military material shortfalls during a US-China conflict. Both the second and third war scenarios found that the following nine materials have the highest shortfall risk: antimony, bismuth, cobalt, niobium (columbium), metallurgical-grade fluorspar, acid-grade fluorspar, iridium, nickel, and titanium sponge.

Counterarguments

The greatest downside risk to publicly releasing this information would be enabling foreign adversaries to better understand the US government's conflict assumptions and supply chain weaknesses, which would enable adversaries to both better prepare for conflict with the United States and undermine US material supply chains. However, given the low classification level of the biennial stockpile assessment (“official government business”), the US government seems to view control of such information as not vital to US national security, or possibly that such information is already well understood by US adversaries. Furthermore, the government’s seemingly low concern about releasing material shortfall projections is illustrated by the public availability of the Department of Defense’s 2015 biennial stockpile assessment, and the government’s seemingly low concern about releasing the military’s annual material usage is illustrated by the public availability of the Department of Defense’s “Reconfiguration of the National Defense Stockpile Report to Congress” from 2009.

Yet, current government practices on releasing information should not be considered best government practices. In a 1949 study on “The Domestic Mining Industry of the United States in World War II,” John D. Morgan, Jr., who would later become special assistant to the assistant director for materials in the Office of the Defense Mobilization, wrote that the US government releases too much information on its mineral industry, specifically engineering and technical information. But, he also said, “For an industry mobilization plan to be effective it must be known to the industry years in advance of actual fighting.” Thus, the main benefit of releasing information on material shortfalls is helping the defense industrial base better prepare for war, while the main risk of releasing such information is helping American adversaries better understand US supply chain weaknesses, which they can target.

American adversaries, especially China, however, already understand US supply chain weaknesses as demonstrated by China’s targeted export controls on gallium, germanium, and graphite, as well as Chinese Communist Party outlets openly highlighting US supply chain weaknesses, like in rare earths. Therefore, the risk of adversaries understanding US supply chain weaknesses has become a reality. On the other hand, the defense industrial base is still unprepared for war, although it is increasingly aware of possible shortages in end-use defense goods, such as platforms and munitions, from various conflicts. But, the defense industrial base seems largely unaware of the possible shortfall quantities for individual materials necessary to build such platforms and munitions in a US-China war. This information will benefit the defense industrial base in preparing it for a possible US-China war.

Thus, the benefits of publicly releasing the biennial stockpile assessment, the US military’s projected shortfall quantities for individual materials, and the US military’s annual usage of individual materials seem to outweigh the risks, helping inform whether the US military has enough minerals for a US-China war.

Conclusion

Moving forward, the Department of Defense should publicly release its biennial stockpile assessment. The Department of Defense should also release information on the shortfall quantities for individual materials, as well as information on the US military’s annual usage of individual materials. This information will offer more insight into what materials the US military relies on most and what materials the US military will most likely have shortfalls of during a possible US-China war. With this information, US policymakers could better understand the military’s supply chain risks and pursue risk mitigation policies. Furthermore, the defense industrial base could preemptively stockpile materials with high shortfall risks before the outbreak of a conflict, enabling the defense industry to better support the war effort.

In The Scientific Monthly in 1918, Joseph E. Pogue, then associate professor of geology and mineralogy at Northwestern University, wrote the following: “Preparedness [for war]…must anticipate the organized use of every mineral resource essential to war, which means practically every mineral resource. This involves study, investigation, exploration, organization, and conservation-rigorous, complete, scientific—which must be inspired and guided by the government. Much has already been done; much remains. And as mineral resources in the future will be more significant in determining the balance of power among nations than they are to-day, this problem becomes increasingly important at time goes on.” His recommendation then remains true today.